Carpenter Nature Center Wood Thrush Research

Presented by Ella Mahnke, CNC Intern 2025

“Whenever a man hears it he is young, and Nature is in her spring; wherever he hears it, it is a new world and a free country, and the gates of Heaven are not shut against him.” – Henry David Thoreau

Learn About... Appearance Habitat Migration Bird Banding Nets Nano Tags Tagging Eligibility Why? What’s Next?

Carpenter Nature Center is committed to protecting the land and the creatures that call it home. The global Wood Thrush population has been declining since the 1950s and scientists are trying to figure out why. Many factors could be at play including habitat degradation, brood parasitism, and climate change. By joining the international Wood Thrush Research Project, we are helping discover what makes their numbers grow and what pressures put them at risk. This research guides our conservation efforts and deepens our commitment to ensuring that both the land and its wildlife thrive for generations to come.

Wood Thrush “101”

The Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina) is often regarded as having one of the most beautiful songs in North America. Its haunting, flute-like melodies echo through the forest during the early morning and evening hours, creating enchanting melodies. The song is more than just a soothing lullaby, it plays a vital role in the bird’s behavior. Male Wood Thrushes sing their songs to establish territory and attract mates, often beginning their serenades before a female arrives. During the breeding season, males also engage in countersinging with their partners, reinforcing pair bonds and coordinating nesting activities.

Appearance

If you hear a beatiful tune and you want confirm if the singer is a Wood Thrush, look for a medium sized bird, about the size of a robin. According to The Birds of North America, Wood Thrush have cinnamon brown feathers on their back, white feathers on their belly, and black spots speckled along their sides.

Habitat

During the spring and summer, Wood Thrushes settle in deciduous forests throughout the eastern United States. They nest in areas with tall trees and canopies with open space below, especially near streams or moist woodlands. While they prefer undisturbed habitat, they’re surprisingly adaptable and can be spotted nesting in parks and older suburban areas with plenty of mature trees. On the forest floor, they forage for insects, snails, and berries, contributing to forest health by dispersing seeds and controlling insect populations. After a female is dazzled by her counterparts’ captivating melodies, she builds a cup-shaped nest, often low in a tree or shrub, using mud, leaves, and grasses.

Migration

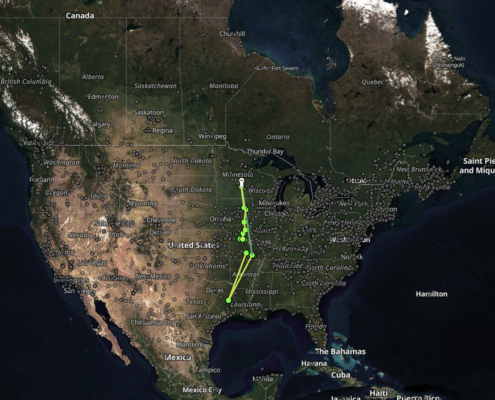

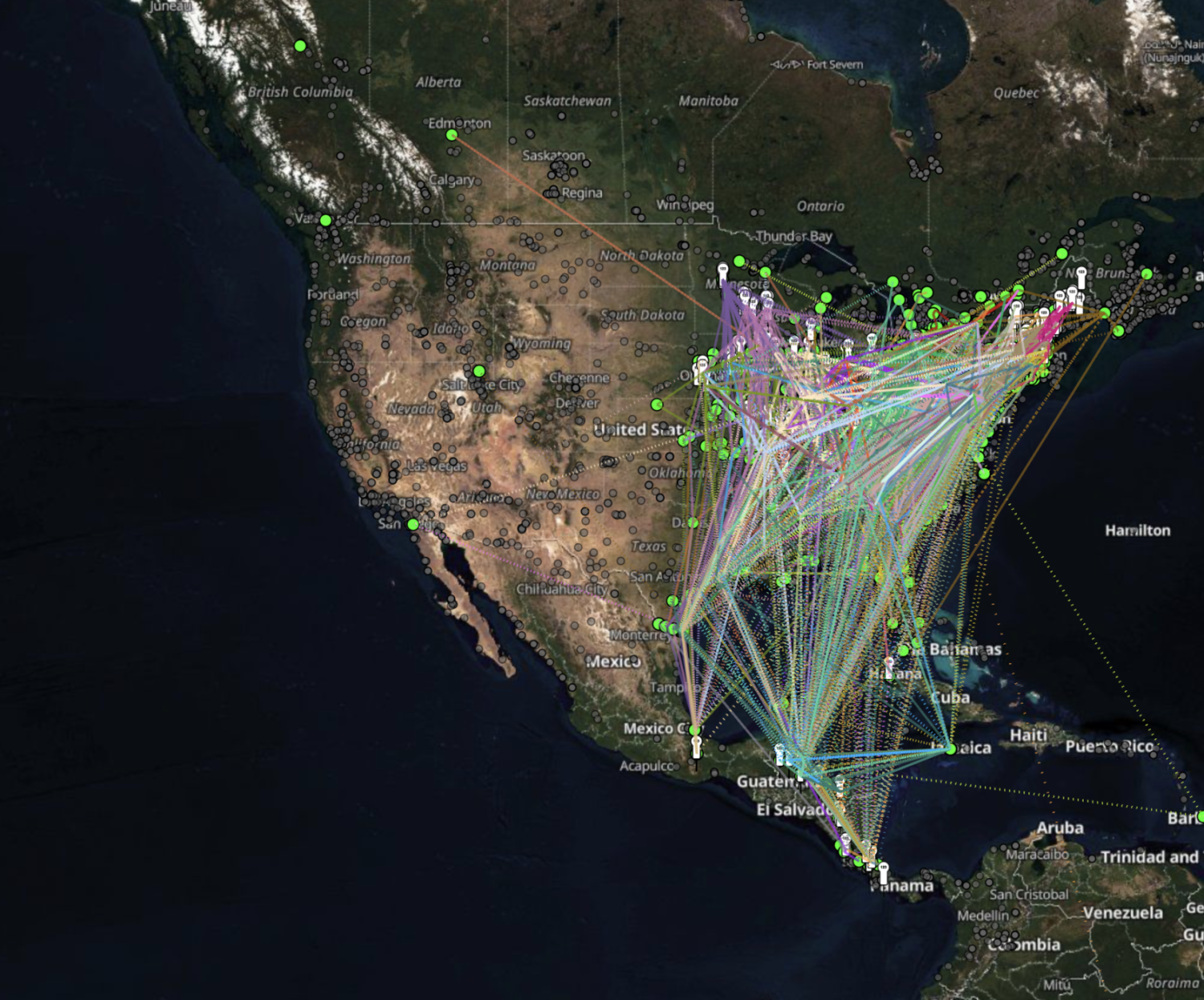

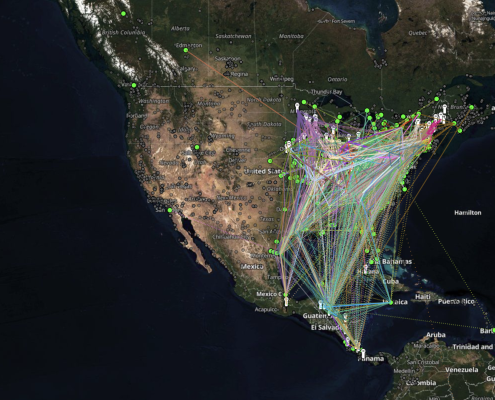

Migration is another fascinating part of the Wood Thrush’s life. These birds travel at night, using the stars to navigate while avoiding daytime predators. In the fall, they follow major flyways like the Mississippi and Central routes, heading south. Thanks to the tracking technology of the Motus Wildlife Tracking System, we now know many of our local Wood Thrush love to spend winter in the lowland forests of Honduras and Venezuela. Just like us, they love a tropical vacation! Wood Thrush will winter in shade grown Coffee Farms as they provide plenty of predator protection and protein-filled bugs to fuel their eventual flight home.

From their stunning song to their cross-continental journeys, Wood Thrushes are one of the most alluring songbirds in our forests. Whether you hear their call echoing through the trees or spot one foraging along a quiet trail, the experience is always memorable.

Threats

Unfortunately, Cowbirds often invade the nests that Wood Thrushes work so hard on to call home. Cowbirds are brood parasites, meaning they trick other birds into caring for their young. According to The Birds of North America, Cowbirds will lay their own eggs in the Wood Thrushes nest, leaving them there to be cared for by the Wood Thrush. The take away the Wood Thrushes attention from their own fledglings. Cowbirds will also occasionally push the Thrush eggs out of the nest, harming population numbers.

Forest fragmentation in both their summer and wintering grounds are also a threat to Wood Thrush population. This makes them more vulnerable to unwelcome Cowbird guests. According to The Audubon Field Guide, climate change is adding new pressures by shifting weather patterns which can affect migration timing, reduce insect populations they rely on for food, and alter the forests they call home.

Acid rain is another threat. According to the Cornell Chronicle, “the wood thrush is less likely to attempt to breed in regions that receive high levels of acid rain.” These regions have less calcium in their soil and have less insects that the Wood Thrush need for food. Calcium plays an essential role in producing strong eggshells and is an overall important vitamin in their diet.

Wood Thrush Research at CNC

The Wood Thrush, known in bird banding shorthand as “WOTH” (from the first two letters of each word in its name), is the focus of a continent-wide research effort known as the WOTH Party. This collaboration spans between North and South America, including work by Carpenter Nature Center in both Wisconsin and Minnesota. The goal is to better understand when Wood Thrushes travel, where they return to, how long they survive, and which habitats are most important for their survival, critical questions for a species whose populations are steadily declining.

Nets

Field teams use a single mist net set up in prime Wood Thrush habitat. To attract birds, speakers play recorded Wood Thrush calls on either side of the net, along with a decoy to spark territorial responses. Captured birds are carefully extracted from the net, which has been given a deeper pocket to prevent larger birds, like Wood Thrushes, from bouncing out, and then banded with a traditional metal band before receiving a high-tech “fanny pack” called a nano tag. All banding, marking, and sampling is being conducted under a federally authorized Bird Banding Permit issued by the U.S. Geological Survey’s BBL.

Nano Tags

Nano tags are small, white radio transmitters designed to sit on the bird’s lower back. Each has a unique frequency and time delay, allowing Motus Wildlife Tracking System towers to detect and identify individual birds as they pass. These tags have a limited battery life, ours last for about 2 years. One Wood Thrush tagged by CNC was later recorded in Honduras before returning to the exact same spot in our area the following summer.

Tagging Eligibility

To be eligible for tagging, a Wood Thrush must weigh at least 45 grams, a requirement the majority of healthy northern birds can easily meet. Southern Wood Thrush sometimes do not meet this requirement, possibly due to Bergmann’s rule, the tendency for animals in colder climates to be larger.

Every tagged Wood Thrush helps us piece together the story of where these birds go, what they need, and how we can help them thrive. The more we learn, the better we can protect the forests and habitats they depend on, so future generations can enjoy the Wood Thrush’s world-renowned song.

Why? What’s Next?

The next step is to gather more data on where Wood Thrushes travel, how long they stay in each location, and what they need to survive in each season. This information will help identify the most critical points in their journey where they are most vulnerable. By learning exactly where Wood Thrushes stop during migration and where they spend the winter, researchers can better protect the places that matter most to them. Migration is a long and risky journey, and these birds rely on healthy habitats for food and shelter at every stop. If scientists discover that a large group of Wood Thrushes spends the winter in a particular forest, that area can be prioritized for conservation.

The data gained from all the groups in this research project will be collected and sorted by the US Fish and Wildlife service.

Protecting these key sites not only helps these birds but also many other species that share the same habitat. Once these areas are known, conservation groups and land managers can focus efforts to keep them from being lost to logging, farming, or development. The hope is not only to stop the Wood Thrush’s decline but to help its numbers grow so future generations can enjoy the Wood Thrush’s world-renowned song.

References

Canada Birds. Wood Thrush. Motus. map. Retrieved 2025, from https://motus.org/dashboard/#.

Jennifer Vieth, CNC Executive Director

Roth, R. R., M. S. Johnson, and T. J. Underwood. 1996. Wood Thrush (Hylocichla mustelina). In The Birds of North America, No. 246 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA, and The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, D.C.

Segelken, R., & August 15, 2002. (2002, August 15). Songbird population declines linked to acid rain, Cornell Ecologists Report. Cornell Chronicle. https://news.cornell.edu/stories/2002/08/songbird-population-declines-linked-acid-rain

Shoshana Schmit, CNC Intern 2025

Wells, J. & Wells, A. (2022). The Mystery of a 10 p.m. Late June Wood Thrush Call. Boothbay Register. https://www.boothbayregister.com/article/mystery-10-pm-late-june-wood-thrush-call/162255

Wood Thrush. Audubon. (2025, May 29). https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/wood-thrush